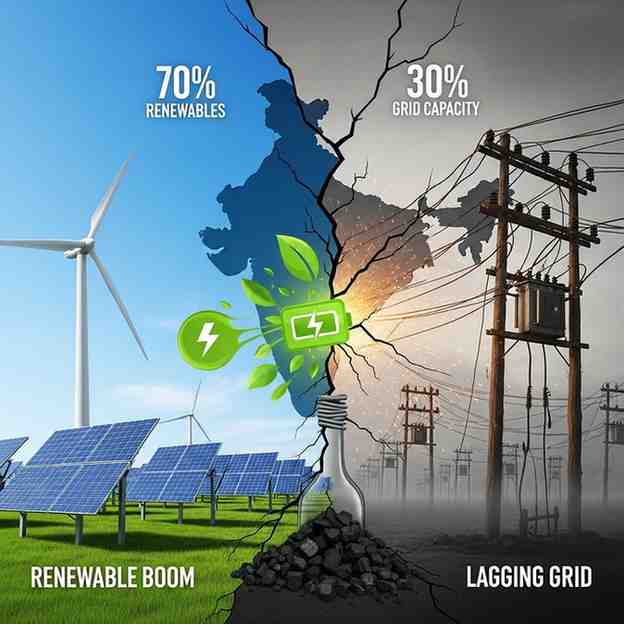

India’s renewable energy transition is frequently showcased as a global success story. Installed renewable capacity has expanded from about 75 GW in 2015 to nearly 250 GW by 2025, driven by rapid solar and wind deployment, competitive tariffs, and strong political signalling. Yet beneath this impressive expansion lies a structural weakness that now threatens to slow the momentum: India’s electricity grid and transmission infrastructure are not keeping pace with renewable generation. As a result, curtailment is rising, capacity is being stranded, and investor confidence is under strain — turning the grid into the most critical bottleneck in India’s green journey.

When generation races ahead of evacuation

Renewable energy projects, particularly solar and wind, can be planned, bid out and commissioned within a year. Transmission infrastructure, by contrast, requires far longer lead times — often two to four years — due to land acquisition, forest clearances, wildlife permissions and social resistance. This asymmetry has produced a widening gap between power generation and evacuation capacity.

Between 2019 and 2025, India’s solar capacity alone nearly tripled, growing at around 24% annually. Over the same period, transmission capacity expanded at barely one-third that pace. The outcome is a familiar paradox: power is being generated but cannot be transported efficiently to demand centres. This mismatch undermines the very logic of large-scale renewable deployment.

Curtailment: the hidden brake on clean energy

The consequences of this imbalance are now visible across several states. Rajasthan has witnessed daytime solar curtailment of around 4 GW during peak months in 2025 due to congestion in evacuation corridors. Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra have reported curtailment levels ranging from 10% to 30% during solar peak hours.

Nationally, nearly 50 GW of renewable capacity is estimated to be stranded because transmission links are not yet operational. For developers, this translates into lost revenues, payment delays and higher financing risk. Over time, repeated curtailment erodes investor confidence, raises the cost of capital and weakens the economics of future projects — directly affecting India’s climate targets.

Why existing policy tools fall short

The government has not been inactive. Initiatives such as Green Energy Corridors, General Network Access (GNA), waiver of inter-state transmission system charges, and the vision of “one nation, one grid, one price” have all aimed to improve grid integration. Yet these tools have struggled to overcome the core problem: fragmented planning.

Generation and transmission continue to be planned in silos. Renewable projects are auctioned aggressively, while transmission planning often lags behind actual capacity addition. Energy storage — frequently presented as a solution to both variability and congestion — remains nascent. Against a target of around 400 GWh of storage by 2031–32, actual deployment is still modest due to high upfront costs and supply chain constraints.

Land, environment and the Right of Way dilemma

Transmission expansion is not merely a technical exercise; it is deeply entangled with land politics and social consent. Securing Right of Way (RoW) — the limited legal right to pass transmission lines over private land — remains one of the most persistent obstacles.

Although transmission projects are exempt from prior environmental clearance under the Environmental (Protection) Rules, 1986, they must still navigate forest approvals, wildlife safeguards, state land laws and local opposition. Compensation disputes are common. Legal norms often provide relatively low compensation, while landowners demand market-linked amounts, leading to prolonged litigation and delays.

A Ministry of Power committee as early as 2005 recommended higher compensation norms — up to

Month: Current Affairs - January 15, 2026

Category: