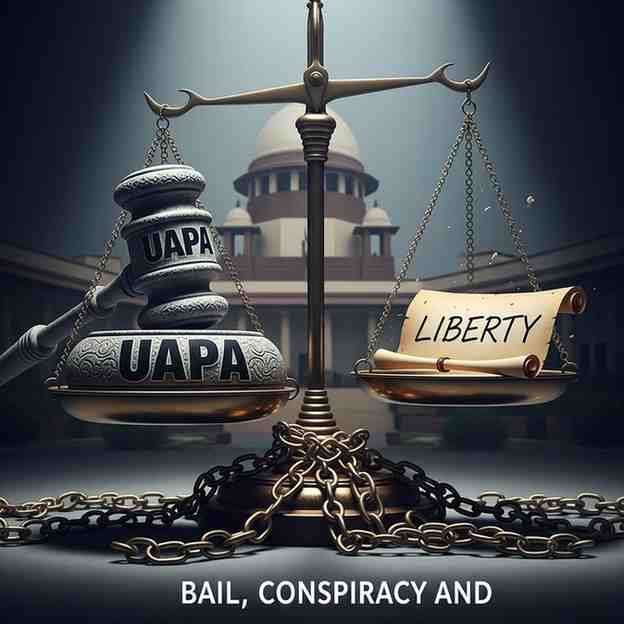

On January 5, 2026, the Supreme Court of India delivered a judgment that will significantly influence how Indian courts balance civil liberties against national security. By refusing bail to student activists Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam in the alleged “larger conspiracy” behind the February 2020 Delhi riots, the Court underscored a hard constitutional truth: once an offence is framed under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act , bail jurisprudence shifts from ordinary criminal law to a far stricter statutory terrain.

Riots as alleged conspiracy, not spontaneous violence

The fulcrum of the judgment lies in the Court’s acceptance, at the prima facie stage, of the prosecution’s claim that the riots were not a sudden eruption of communal anger but the culmination of prior planning. According to the State, protest mobilisation following the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Bill in December 2019 evolved into a coordinated strategy involving road blockades, messaging, and escalation designed to provoke confrontation.

This characterisation was decisive. Had the violence been treated as spontaneous disorder, conventional penal law would apply. Once framed as an organised conspiracy threatening public order and security, the legal lens shifted to UAPA — where Parliament has consciously imposed a higher threshold for liberty.

How UAPA reshapes the bail inquiry

Section 43D(5) of the UAPA creates a statutory bar on bail if courts find “reasonable grounds” to believe that accusations are prima facie true. The Supreme Court reiterated that at this stage it is not assessing guilt or testing defences. Its role is limited to examining whether, on a plain reading, the prosecution material legally supports the alleged offences.

Once that threshold is crossed, factors such as the seriousness of allegations and the accused’s role outweigh conventional considerations like parity or length of custody. This, the Court noted, reflects legislative intent to treat terrorism-related offences differently from ordinary crimes.

Khalid, Imam and the law of conspiracy

A central defence argument for Umar Khalid was his absence from riot-affected areas. The Court rejected this as legally irrelevant. In conspiracy law, physical presence at the scene is unnecessary once participation in planning or direction is alleged. Accepting the prosecution’s portrayal of Khalid as an ideological and strategic coordinator, the Court observed that distance from the site could equally suggest a supervisory role.

In Sharjeel Imam’s case, the Court addressed the idea of “indirect incitement”. Even without explicit calls for violence, outlining actions such as prolonged road blockades — allegedly with knowledge that they could trigger chaos — could, at the bail stage, support an inference of conspiratorial intent. Disclaimers of violence do not neutralise foreseeable consequences embedded in an alleged plan.

Delay, liberty and its limits

Both accused had spent years in custody, and the trial remains distant, with hundreds of witnesses cited. While prolonged incarceration ordinarily strengthens Article 21 claims, the Court held that delay alone cannot override the UAPA bar where a prima facie case exists — particularly when delays are not solely attributable to the prosecution.

Differentiating roles within the same FIR

A crucial doctrinal contribution of the judgment is its role-based approach. While denying bail to Khalid and Imam, the Court granted bail to five co-accused, holding that their alleged roles were peripheral rather than central. Bail, it stressed, depends on individual attribution, not activist identity or blanket conspiracy labels.

Those released remain under strict

Month: Current Affairs - January 08, 2026

Category: